In the September/October 2025 edition of Briarpatch Magazine, I was able to publish a reading list about Ukrainian Resistance to Russian Colonialism. It is reproduced below with additional works I had to cut for length.

I also recently became a board member for Briarpatch, so I strongly encourage you to check out their reporting and consider signing up for a subscription.

In my final class studying international human rights law, I shared my paper analyzing Ukraine’s law on Indigenous people which, while imperfect, protects the territorial and language rights of Crimean Tatars, Karaites and Krymchaks. In the class discussion, a friend and self-proclaimed Marxist wearing a keffiyeh asked if I knew that the Russian language was broadly oppressed in Ukraine. Despite their rightful support for Palestine and correct criticism of colonial governments, they tended to be sympathetic to a different colonial, imperial power by repeating one of Russia’s falsified justifications for engaging in an unprovoked war of aggression.

Expanding our critiques beyond western colonial empire is important as we struggle to find alternatives to any form of oppressive, centralized power. As fascism balloons in our own backyard, we can learn from Ukrainian people actively resisting a fascist authoritarian state. And as we try to comprehend how to dismantle an empire here, we can well be reminded that the problem isn’t one empire or another; rather, the problem is empire itself. As one empire coerces Ukraine into a minerals deal, another empire is currently shooting ballistic missiles at shopping centres in Ukraine.

The following resources have helped me understand Ukrainian resistance as removing itself from under the foot of centuries of a colonial power.

Russian Colonialism 101 (2023)

Until I found the illustrated book, Russian Colonialism 101, by Ukrainian journalist Maksym Eristavi, I hadn’t heard of Russian history explained as colonial power. In the Western anti-colonial, anti-capitalist circles in which I found myself, the Soviet Union was generally either tolerated or praised, with Joseph Stalin’s violent purges considered one of the only dark spots marring this alternative to capitalism. I knew little about its predecessor, the Russian Tsarist Empire, or the current Russian Federation. This guidebook (basically a reading list of its own) explains that the past three iterations of Russian rule – from the Tsars to the Bolsheviks to the Vladimir Putin regime – have employed the same colonial tactics to control and oppress Indigenous nations neighbouring and within Russia’s borders. When Russian prisoners of war are released they are often photographed holding flags for Tsarist Russia, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and the Russian Federation all at once. The book demonstrates that the current war on Ukraine is far from a singular project of a power-hungry dictator, but an unfortunate feature of Russian colonial statehood.

Matryoshka of Lies: Ending Empire (2024)

The Matryoshka of Lies podcast, hosted by Maksym Eristavi and Ukrainska Pravda news outlet dives into lesser-known histories of Russian colonialism. The season-one finale, Ending Empire, touches on Russia’s expansion into Alaska in the late 1700s, where they extended the same policies of coercion and enslavement they used on Indigenous nations of Northern Asia. (Tlingit resistance to this Russian colonialism is best captured by Gord Hill in The 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance Comic Book: Revised and Expanded.)

In part, the purpose of the episode and the podcast as a whole is to allow a western audience to better understand Russian colonialism as akin to the genocidal horrors of European colonialism that many North Americans are just starting to grapple with. Similar to many radicals in North America calling for an end to U.S. hegemony and violence through an end of the American Empire, this episode suggests that a “total reset in what is now the Russian Federation” is the only way to end these continuing colonial expansionary tactics.

A Brief History of a Long War: Ukraine’s Fight Against Russian Domination (2025)

Policies of food control and forced starvation have long been a genocidal policy of colonial governments, from Canada’s purposeful extermination of Indigenous food sources, to Israel’s current explicit weaponization of food in Gaza. The Holodomor (meaning ‘death by starvation’) occurred in 1932-33 in Ukraine and led to the deaths of upwards of a fifth of all Ukrainians. Soviet policies forced the collectivization of farms, imprisoned or killed people for hiding or ‘stealing’ grain, and instituted restricted travel so Ukrainians could not access other food sources.

Whereas most narratives of the war start in 2022, or maybe 2014, Mariam Naiem’s graphic novel puts Russia’s war on Ukraine into perspective from the very beginning of Ukrainian nationhood. It unravels the long history of policies meant to extinguish Ukrainian sovereignty movements that threatened Russian control over valuable Ukrainian natural resources: from the Holodomor to policies meant to marginalize the Ukrainian language, to Russia’s invasion once Ukraine shifted into the European sphere of influence. This introduction to the history of the region helps give context to the war by explaining the centuries of Russian empire and Ukrainian resistance.

While the Western left has generally expressed support for Ukraine, in some anti-imperialist circles, dialogue is often immobilized when someone associates Ukraine with NATO, Nazis, or nukes. In this interview, Hanna Perekhoda, a Ukrainian socialist and historian, succinctly addresses some of the most controversial among these stumbling blocks. She explains supposed Russian-language oppression and Russophobia is akin to the anti-white racism rhetoric rising in the West. Perekhoda speaks to Putin’s claim that Ukraine is overrun by Nazis, a propagandist justification for the war hearkening back to Second World War mythology. She acknowledges Ukraine’s far right, noting they have repeatedly proven to be a fringe movement. Given that problems with the far right exist everywhere, she questions whether this justifies a full-scale invasion or a withholding of military support or other aid. She notes that what really risks a rise in fascism is a long-standing war waged by a fascist Russian regime where common Ukrainians are radicalized by years of military occupation and systematic oppression. As Perekhoda makes clear, what is needed is support for Ukrainian lives, autonomy, and resistance.

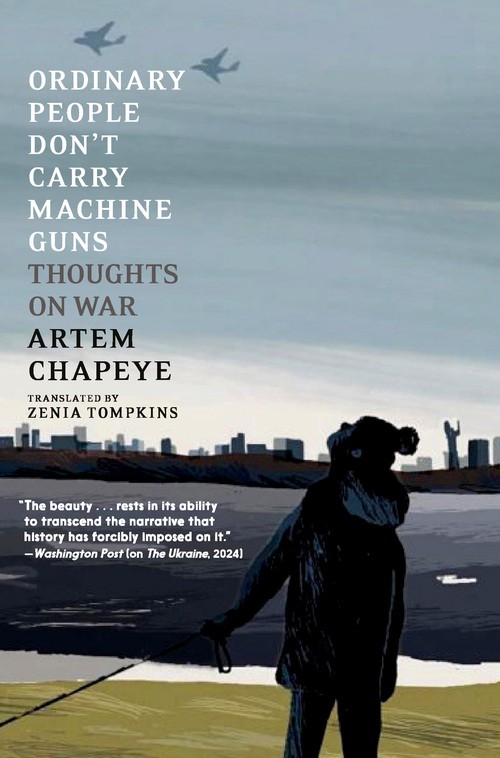

Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns: Thoughts on War (2025)

Ukrainian author Artem Chapeye gives a contemporary account of what it is like to be on the receiving end of a colonial war of expansion. As a self-proclaimed pacifist, leftist, and feminist, Chapeye joined Ukraine’s military in 2022. After politely admonishing Western anti-imperial leftists for their lack of critique of other powers as compared to their rigorous critique of the American Empire, Chapeye addresses the privilege of pacifism that judges Ukrainian (and other) resistance; anarchist traditions of Ukraine’s historical resistance to empire; navigating the tension of being against the authoritarian dangers of nationalism while fighting for a civic – rather than ethnic – community currently under a nation-state; and the impossible psychological toll of war. Speaking to himself as much as to Western audiences, Chapeye explains Ukrainian resistance as follows: “We can either fight back now, with the losses that necessarily accompany this, or remain the colony of an empire for another hundred years.” His book explains his decision to fight against Russian invasion is not because of a guaranteed win, but because of the moral imperative to fight fascism in all its forms.

ADDITIONAL WORKS

Where Russia Ends (film) (2024)

Makhno: Ukrainian Freedom Fighter (graphic novel) (2022)

Hey Waitress! – Helen Potrobenko

Putin’s Trolls – Jessikka Aro (2022)

Without the State – Emily Channell-Justice

Five Stalks of Grain (graphic novel) (2022)